29.3.11

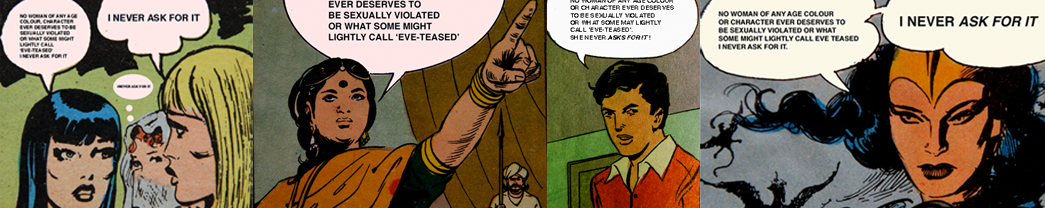

ACTION HEROES BELIEVE IT'S IMPORTANT TO RE- EXAMINE SWEAR WORDS:

26.3.11

Beyond the Digital-Reflecting from the Beyond

First posted here

By Maesy Angelina in the Digital Natives

After going ‘beyond the digital’ with Blank Noise through the last nine posts, the final post in the series reflects on the understanding gained so far about youth digital activism and questions one needs to carry in moving forward on researching, working with, and understanding digital natives.

Throughout the series, I have argued the following points. Firstly, the 21st century society is changing into a network society and that youth movements are changing accordingly. I have outlined the gaps in the current perspectives used in understanding the current form and proposed to approach the topic by going beyond the digital: from a youth standpoint, exploring all the elements of social movement, and based on a case study in the Global South – the uber cool Blank Noise community who have embraced the research with open arms. The methodology has allowed me to identify the newness in youth’s approach to social change and ways of organizing. Although I do not mean to generalize, there are some points where the case study resonates with the broader youth movement of today. In this concluding post, I will reflect on how the research journey has led me to rethink several points about youth, social change, and activism.

While social movements are commonly imagined to aim for concrete structural change, many youth movements today aim for social and cultural change at the intangible attitudinal level. Consequently, they articulate the issue with an intangible opponent (the mindset) and less-measurable goals. Their objective is to raise public awareness, but their approach to social change is through creating personal change at the individual level through engagement with the movement. Hence, ‘success’ is materialized in having as many people as possible involved in the movement. This is enabled by several factors.

The first is the Internet and new media/social technologies, which is used as a site for community building, support group, campaigns, and a basis to allow people spread all over the globe to remain involved in the collective in the absence of a physical office. However, the cyber is not just a tool; it is also a public space that is equally important with the physical space. Despite acknowledging the diversity of the public engaged in these spaces, youth today do not completely regard them as two separate spheres. Engaging in virtual community has a real impact on everyday lives; the virtual is a part of real life for many youth (Shirky, 2010). However, it is not a smooth ‘space of flows’ (Castells, 2009) either. Youth actors in the Global South do recognize that their ease in navigating both spheres is the ability of the elite in their societies, where the digital divide is paramount. The disconnect stems from their acknowledgementthat social change must be multi-class and an expression of their reflexivity in facing the challenge.

The second enabling factor is its highly individualized approach. The movement enables people to personalize their involvement, both in terms of frequency and ways of engagement as well as in meaning-making. It is an echo of the age of individualism that youth are growing up in, shaped by the liberal economic and political ideologies in the 1990s India and elsewhere (France, 2007). Individualism has become a new social structure, in which personal decisions and meaning-making is deemed as the key to solve structural issues in late modernity (Ibid).

In this era, young people’s lives consist of a combination of a range of activities rather than being focused only in one particular activity (Ibid). This is also the case in their social and political engagement. Very few young people worldwide are full-time activists or completely apathetic, the mainstream are actually involved in ‘everyday activism’ (Bang, 2004; Harris et al, 2010). These are young people who are personalizing politics by adopting causes in their daily behaviour and lifestyle, for instance by purchasing only Fair Trade goods, or being very involved in a short term concrete project but then stopping and moving on to other activities. The emergence of these everyday activists are explained by the dwindling authority of the state in the emergence of major corporations as political powers (Castells, 2009) and youth’s decreased faith in formal political structures which also resulted in decreased interest in collectivist, hierarchical social movements in favour of a more individualized form of activism made easier with Web 2.0 (Harris et al, 2010).

A collective of everyday activists means that there are many forms of participation that one can fluidly navigate in, but it requires a committed leadership core recognized through presence and engagement. As Clay Shirky (2010: 90) said, the main cultural and ethical norm in these groups is to ‘give credit where credit is due’. Since these youth are used to producing and sharing content rather than only consuming, the aforementioned success of the movement lies on the leaders’ ability to facilitate this process. The power to direct the movement is not centralized in the leaders; it is dispersed to members who want to use the opportunity.

This form of movement defies the way social movements have been theorized before, where individuals commit to a tangible goal and the group engagement directed under a defined leadership. The contemporary youth movement could only exist by staying with the intangible articulation and goal to accommodate the variety of personalized meaning-making and allow both personal satisfaction and still create a wider impact; it will be severely challenged by a concrete goal like advocating for a specific regulation. Not all youth there are ‘activist’ in the common full-time sense, for most everyday activists their engagement might not be a form of activism at all but a productive and pleasurable way to use their free time - or, in Clay Shirky’s term, cognitive surplus (2010).

Revisiting my initial intent to put the term activism under scrutiny, I acknowledge this as a call for scholars to re-examine the concepts of activism and social movements through a process of de-framing and re-framing to deal with how youth today are shaping the form of movements. Although the limitations of this paper do not allow me to directly address the challenge, I offer my own learning from this process for the quest of future researchers.

The way young people today are reimagining social change and movements reiterate that political and social engagement should be conceived in the plural. Instead of “Activism” there should be “activisms” in various forms; there is not a new form replacing the older, but all co-existing and having the potential to complement each other. Allowing people to cope with street sexual harassment and create a buzz around the issue should complement, not replace, efforts made by established movements to propose a legislation or service provision from the state. This is also a response I offer to the proponents of the aforementioned “doubt” narrative.

I share the more optimistic viewpoint about how these new forms are presenting more avenues to engage the usually apathetic youth into taking action for a social cause. However, I also acknowledge that the tools that have facilitated the emergence of this new form of movement have existed for less than a decade; thus, we still have to see how it evolves through the years.

Hence, I also find the following questions to be relevant for proponents of the “hope” narrative. Social change needs to cater to the most marginalized in the society, but as elaborated before, the methods of engagement both on the physical and virtual spaces are still contextual to the middle class. Therefore, how can the emerging youth movements evolve to reach other groups in the society? Since most of these movements are divorced from existing movements, how can they synergize with existing movements to propel concrete change? These are open questions that perhaps will be answered with time, but my experience with Blank Noise has shown that these actors have the reflexivity required to start exploring solutions to the challenges.

The research started from a long-term personal interest and curiosity. In this journey, I have found some answers but ended up with more questions that will also stay with me in the long term. As a parting note before, I would like to share a quote that will accompany my ongoing reflection on these questions.

My advice to other young activists of the world: study and respect history... but ultimately break the mould. There have never been social media tools like this before. We are the first generation to test them out: to make the mistakes but also the breakthrough.

(Tammy Tibbetts, 2010)

This is the tenth and final post in the Beyond the Digital series, a research project that aims to explore new insights to understand youth digital activism conducted by Maesy Angelina with Blank Noise under the Hivos-CIS Digital Natives Knowledge Programme.

23.3.11

Beyond the Digital-Unraveling the Term

first posted here

After discussing Blank Noise’s politics and ways of organizing, the current post explores whether activism is still a relevant concept to capture the involvement of people within the collective. I explore the questions from the vantage point of the youth actors, through conversations about how they relate with the very term of activism.

Youth's Popular Imagination of Activism

As a start, I need to clarify that ‘activism’ is not a concept that the participants are generally concerned with. For a majority of them, the conversation we had was the first time they thought of what the term means and reflect whether their engagement with Blank Noise is activism. Regardless of whether one identifies Blank Noise as a form of activism or not, all participants share a popular idea of what activism is.

Generally speaking, at an abstract level all participants saw activism as passionately caring about an injustice and taking action to create social change. At a more tangible level, all participants mentioned three elements as popular ideas about doing activism. The first is the existence of a concrete demands as a solution to the identified problem, such as asking for service provision or state regulations. Since these demands are structural, activism is also seen dealing with formal authority figures in the traditional sense of politics, the state. The second is the intensity and commitment required to be an activist, for many participants being an activist means having prolonged engagement, taking risks, and making the struggle a priority in one’s life. In other words, being an activist means “... being neck-deep, spending most if not all of your time, energy, and resources for the cause” (Dev Sukumar, male, 34). The third element relates to the methods, called by some as ‘old school’: shouting slogans, holding placards, and doing marches on the streets – all enacted in the physical public space. This popular imagination of activism becomes the orientation for participants in deciding whether Blank Noise is a form of activism and whether they are activists for being involved in it.

Activism as the Intention and Action

“I have an idea of what activism is but not what it exactly looks like.”

(Apurva Mathad, male, 28).

For those who think that Blank Noise is a form of activism, there was a differentiation between the idea at the abstract level and how it is manifested at a more tangible level. The definition of activism is the abstract one, while the popular ideas of doing activism do not define the concept but present the most common out many possible courses of actions. Blank Noise is fulfils all the elements in the abstract definition: a passion about an injustice, having an aim for social change, and acting to achieve the aim. Hence, Blank Noise is activism, but the way it manifests itself does not adhere to the popular imagination of doing activism. The distinction between Blank Noise’s methods with popular ones was emphasized, along with the difference in articulating goals.

Interestingly, not all participants who share this line of thinking called themselves as activists for being involved in an activism. Again, it must be reiterated that no participants ever really thought of giving a name to their engagement prior to the interview. Instead of saying ‘I am an activist’, they said ‘I guess I could be called an activist’ for the fact that they are sharing the passion and being actively involved in a form of activism, albeit in an unconventional manner.

Those who would categorize Blank Noise as activism but not call themselves activists related with a particular element on the popular idea of doing activism, which is getting “neck-deep”. They were helpers, volunteers, idea spreaders, but not an activist because their lives are not dedicated for the cause or their involvements were based on availability. On the other hand, these participants all said that Jasmeen is an activist for being completely dedicated to Blank Noise from its inception until today.

Activism as Particular Ways of Doing and Being

“What are the repercussions if activism is so fluidly defined? It can mean not questioning

privilege... not seeing the class divisions and still call yourself activist.”

(Hemangini Gupta, female, 29).

Most participants did not consider Blank Noise as an activism. Generally, this can be explained by the discrepancies between Blank Noise and the popular imagination on the tangible ways of doing activism. Blank Noise does not propose a concrete solution or make concrete demands to an established formal structure nor did it march on the streets and make slogans. However, the underlying attitude to this point of view is not of a younger generation finding the ‘old’ ways of doing activism obsolete. Rather, there was an acknowledgement that the issue itself causes the different ways of reading an issue and taking actions to address it.

Furthermore, there is an appreciation to the achievements and dedication of activists that deterred them from calling themselves activists. These people referred to their occasional participation and the fact that Blank Noise is not the main priority in their lives as a student or young professional despite being a cause they are passionate about. As reflected in the opening quote, being an activist for some participants also means deeply reflecting on their self position in terms of class, acknowledging their privileges, and putting themselves in a position that will enable them to imagine the experience of people who are also affected by the issue but has a different position in the society. In other words, being an activist is not just about doing but also about critically reflecting on one’s position in relation to the issue and how it influences the way an issue is being pushed forward. Thinking that they are not up to these standards, these youth choose to call themselves ‘volunteers’, ‘helpers’, or ‘supporters’.

Youth: The Activist, the Apathetic, and the Everyday

“Blank Noise is a public and community street arts collective that is volunteer-led and attempts to create public dialogue on the issue of street sexual violence and eve teasing.”

(Jasmeen Patheja)

“... a group of people against street sexual harassment and eve teasing.”

(Kunal Ashok, men, 29)

“... an idea that really works.”

(Neha Bhat, 19)

As clarified before, the participants did not use the words ‘movement’ and very few used ‘activism’ during our conversations. Instead, the terms they used to describe Blank Noise are represented in the quotes above: collective, community, group, project, and even as an idea. These phrases do not carry the same political baggage that ‘movement’ or ‘activism’ would; they also do not conjure a particular imagination that the other two terms would. These phrases are de-politicized and informal; they imply fluidity, lack of hierarchy, and room for manoeuvre.

The implied meanings in the terms reflect the debates on the average youth and political engagement. For the past decade, various youth scholars criticized the dichotomy of youth as either activists or apathetic in explaining the global trend of decreased youth participation in formal politics. The activists are either politically active Digital Natives engaged in new forms of social movements influenced heavily by new media or sub-cultural resistances, which only account for a fraction of the youth population that are mostly completely apathetic. This dichotomy ignored the ‘broad “mainstream” young people who are neither deeply apathetic about politics on unconventionally engaged’ (Harris et al, 2010).

These mainstream young people actually are socially and politically engaged in ‘everyday activism’ (Bang, 2004; Harris et al, 2010). These are young people who are personalizing politics by adopting causes in their daily behaviour and lifestyle, for instance by purchasing only Fair Trade goods, or being very involved in a short term concrete project but then stopping and moving on to other activities. The emergence of these everyday activists are explained by the dwindling authority of the state in the emergence of major corporations as political powers (Castells, 2009) and youth’s decreased faith in formal political structures which also resulted in decreased interest in collectivist, hierarchical social movements in favour of a more individualized form of activism (Harris et al, 2010). Internet and new media technologies are credited as an enabling factor, being a space and a medium for young people to express their everyday activism.

All of the research participants, perhaps with the exception of Jasmeen as the only one who has constantly been the driver Blank Noise its entire seven years, are these everyday makers, people who were involved with the Blank Noise either on a daily basis as a commentator, one-time project initiator and leader, or people who were active when they are available but remain dormant at other times. Blank Noise is a space where these individual forms of engagement could be exercised while remaining as a collective. The facilitation is not only by the flexibility of coming and going, but also the lack of rigid group rules and the approach of allowing Blank Noise to be interpreted differently by individuals. Considering that the mainstream urban youth are everyday makers who would not find ‘old’ or ‘new’ social movements appealing, this can be the reason why Blank Noise became so popular among youth; however, I would also argue that the fact that Blank Noise is the first to systematically address eve teasing is a determining cause.

The implications of this finding, together with other concluding thoughts, will be shared in the next and final post in the Beyond the Digital series.

This is the ninth post in the Beyond the Digital series, a research project that aims to explore new insights to understand youth digital activism conducted by Maesy Angelina with Blank Noise Project under the Hivos-CIS Digital Natives Knowledge Programme.

22.3.11

Beyond the Digital-The Many Faces Within

Blank Noise, as many other digital native collectives, may seem to be complete horizontal at first glance. But, a closer look reveals the many different possibilities for involvement and a unique way the collective organize itself.

One day, during an afternoon stroll to the M.C. Escher museum in The Hague, I stumbled upon a painting called ‘Fish and Scales’. On the first glance, I saw two big black-and-white fishes and some smaller ones, but on a closer look I found hundreds of fishes, heading to different directions and merging seamlessly into the bigger fishes as their scales. Upon this discovery, I exclaimed out loud, “This is just like Blank Noise!”

No, I do not mean to imply in any way that the Blank Noise Project is like a fish, although it is definitely as fascinating as the painting. Rather, I found that this painting from the master of optical illusion is a great analogy to the structures of Blank Noise.

In the words of Kunal Ashok, one of the male volunteers, the collective consists not only of “people who volunteer or come to meetings, but anyone that have contributed in any way they can and identified with the issue.” In this sense, Blank Noise today consists of over 2,000 people who signed up to their e-group as volunteers.

How does a collective with that many people work? Firstly, although these people are called ‘volunteers’ for registering in the e-group, I would argue that a majority of them are actually what I call casual participants – those who comment on Blank Noise interventions, re-Tweet their call for action, promote Blank Noise to their friends through word of mouth, or simply lurk and follow their activities online. In the offline sense, they are the passers-by who participate in their street interventions or become intrigued to think about the issue afterwards. These people, including those who do the same activities without formally signing up as volunteers, are acknowledged to be a part of Blank Noise as much as those who really do volunteer.

Blank Noise is open to all who shares its concern and values, but its volunteers must go beyond articulating an opinion and commit to collective action. However, Blank Noise applies very little requirement for people to identify themselves with the collective. The main bond that unites them is their shared concern with street sexual harassment. Blank Noise’s analysis of the issue is sharp, but it also accommodates diverse perspectives by exploring the fine lines of street sexual harassment and not prescribing any concrete solution, while the latter is rarely found in existing social movements. The absence of indoctrination or concrete agenda reiterated through the public dialogue approach gives room for people to share different opinions and still respect others in the collective.

Other than these requirements, they are able to decide exactly how and when they want to be involved. They can join existing activities or initiate new ones; they can continuously participate or have on-and-off periods. This is reflected in the variety of volunteers’ motivations, activities, and the meaning they give to their involvement. For some people, helping Blank Noise’s street interventions is exciting because they like street art and engaging with other young people. Many are involved in online campaigns because they are not physically based in any of the cities where Blank Noise is present. Some others prefer to do one-off volunteering by proposing a project to a coordinator and then implementing it. There are people who started volunteering by initiating Blank Noise chapters in other cities and the gradually have a more prominent role. Some stay for the long term, some are active only for several times before going back to become supporters that spread Blank Noise through words of mouth. The ability to personalize volunteerism is also what makes Blank Noise appealing, compared to the stricter templates for volunteering in other social movements.

Any kind of movement requires a committed group of individuals among the many members to manage it. The same applies to Blank Noise, who relies on a group of people who dedicate time and resources to facilitate volunteers and think of the collective’s future: the Core Team. Members of the Core Team, about ten people, are credited in Blank Noise’s Frequently Asked Question page and are part of a separate e-group than the volunteers. In its seven years, the Core Team only went for a retreat once and mostly connected through the e-group. In this space, they raise questions, ideas, and debates around Blank Noise’s interventions, posters, and blog posts. Consequently, for them the issue is not only street sexual harassment but also related to masculinities, citizenship, class, stereotyping, gender, and public space. However, there are also layers in the intensity of the Team members’ engagement.

The most intense is Jasmeen, the founder and the only one who has been with Blank Noise since its inception until today. Jasmeen is an artist and considers Blank Noise to be a part of her practice; she has received funds to work for Blank Noise as an artist. Thus, she is the only one who dedicates herself to BN full time and becomes the most visible among the volunteers and the public eye. According to Jasmeen, she is not alone in managing the whole process within Blank Noise. Since Hemangini Gupta came on board in 2006, she has slowly become the other main facilitator. “It is a fact that every discussion goes through her. I may be the face of it, but I see Hemangini and me working together. We rely on each other for Blank Noise work,” Jasmeen said.

Hemangini, a former journalist who is now pursuing a PhD in the U.S., explains her lack of visibility. “Blank Noise could never be my number one priority because it doesn’t pay my bills, so I can only do it when I have free time and my other work is done.” The same is true for others in the Core Team: students, journalists, writers, artists. Unlike Hemangini who still managed to be intensively involved, they have dormant and active periods like the volunteers.

The Core Team’s functions as coordinators that facilitate the volunteers’ involvement in Blank Noise and ensure that the interventions stay with the values Blank Noise upholds: confronting the issue but not aggravating the people, creating public dialogue instead of one-way preaching. This role emerged in 2006 when the volunteer applications mounted as the result of the aforementioned blogathon. They have also initiated or made Blank Noise chapters in other cities grew. Although some of them have also moved to another city due to work, they remain active touch through online means. Together, the Core Team forms the de-facto leadership in Blank Noise.

I am tempted to describe Blank Noise as having a de-facto hierarchy in its internal organization. The form would be a pyramid, with Jasmeen on top, followed by the coordinators, long-term project-based volunteers, one-off-project-initiator volunteers, and then the casual participants. After all, it was clear from my conversations with the many types of volunteers within Blank Noise that they acknowledge that some people are involved more intensely and carry more responsibilities than others in the collective, that there is an implicit leadership roles. This is also shown by the reluctance of many volunteers to call themselves as an ‘activist’, claiming that the title is only suitable for people within those leadership roles and preferring to call themselves ‘supporters’, ‘part of the group’, or ‘volunteers’ instead.

However, doing this will be a mistake in interpreting the internal dynamics within Blank Noise. Firstly, the line between the types of participation is not as clear-cut as it appears to be. With the exception of Jasmeen, everyone from the coordinators to the one-off volunteers has active and dormant periods depending on what happens in their personal lives; they can shift roles quite easily. Some of Blank Noise coordinators, for instance, are now pursuing higher education abroad and could only be very active when the return to India during the holidays or when the school schedule is not as demanding. During momentary dormant periods, they turn into casual participants because those are the only roles they are able to take. Secondly, a hierarchy implies that casual participants are not important for the collective, whereas they turn out to be the main “target group” and the reason why Blank Noise has grown internally and in the public eye.

This is again a reason why I was so taken by Escher’s painting. There are definitely “big fish” leadership figures, but their scales are actually smaller fishes in different forms, symbolizing how the roles of a person in the collective could shift from “big” to “small” and vice versa depending on your perspective. The many fishes are not depicted horizontally, but also not in a clear hierarchy. Instead, they are interconnected with each other. The type of connection is not very clear and the fishes seem to be swimming in different directions, but they make a cohesive unity. This is the beauty of both Escher’s creation and Blank Noise.

This is the eighth post in the Beyond the Digital series, a research project that aims to explore new insights to understand youth digital activism conducted by Maesy Angelina with The Blank Noise Project under the Hivos-CIS Digital Natives Knowledge Programme.

The photo of M.C. Escher’s painting ‘Fish and Scales’ is borrowed from:

http://www.mathacademy.com/pr/minitext/escher/big.asp?IMAGE=fish_and_scales

Beyond the Digital-The Class Question

Blank Noise aims to be as inclusive as possible and therefore does not identify any specific target groups. Yet, the spaces and the methods they occupy do attract certain kinds of volunteers and public. This raises the class question: what are the dilemmas around class on digital interventions? Are they any different from the dilemmas on street interventions?

My first click to Blank Noise’s main blog was a surprise. Having read so many media coverage about them, I expected to see a professional, minimalist looking website like other women’s organizations[1] where the menu is immediately visible. Instead, I have arrived at the most common and basic form of blogging: the personal blog.

I was greeted by entries on their latest thoughts and activities with photos and text with red font against a black background. I scrolled down a long list of permanent links on the right side of the site and arrived only at its Frequently Asked Questions link on the 28th item while it would be one of the easiest to spot in other websites. For me, this discovery said, “we would like to share our thoughts and activities with you” rather than “we are an established organization and this is what we do”. It is not the space of professionals, but passionate people. As a blogger myself, I recognize the space as being one of my peer’s and immediately felt more attracted to it.

Reflecting on my own position, my familiarity with the space is due to my background as a young, urban, educated, English-speaking woman for whom the Internet is a key part of life. My ‘peers’ who are also attracted to this place apparently share the same background with me. The main demography of Blank Noise’s volunteers, almost equally men and women, are those between 16-35 years, urban, and English speaking (Patheja, 2010). My interviewees were all at least university educated, some in the U.S. Ivy league, and are proficient users of social media, most of them being bloggers or Twitter and Facebook users.

This dominant base reflects the discourse on the ‘youth of India’, which represents only a fragment of India’s vast population of young people. The two narratives on the youth of India are described by Sinha-Kerkhoff (2005) as ‘the haves’ and ‘have-nots’, a reflection on the broader discourse on the deep social economic inequities in India. ‘The have-nots’ are the majority of Indian youth who are struggling with the basic issues of livelihood, health, and education, while ‘the haves’ are painted as the children of liberalization: the mostly urban, middle class, technologically savvy, and highly educated students and young professionals up who maintain a youthful lifestyle up to their 30s.

Although ‘the haves’ only consist 10% of the total youth population, they are the ones identified as the youth of India by popular discourses. Lukose (2008) explained this by stating that youth as a social category in India is linked to the larger sense of India’s transformation into an emerging global economic powerhouse together with Brazil, Russia, and China (popular as BRIC) after its liberal economic reform in the 1990s. India’s information and technology industry is spearheading this transformation, thus it feeds into the discourse of youth as Digital Natives.

Although there are exceptions to this dominant demography, they are far fewer. Does this then mean that Blank Noise is ‘contextually empowering’ (Gajjala, 2004), given that it reaches only ‘the haves’ due to the digital divide and their sites of participation?

The classed nature of the virtual public space is something Blank Noise fully acknowledges. Some interviewees stated that this is why street interventions are so important; they reach people who may not be Internet users. However, people who have been involved in Blank Noise for more than two years acknowledged that class issues are also present in the physical public space.

Dev Sukumar, one of Blank Noise’s male volunteers, explained to me that the British colonial legacy still shape the way public spaces in Bangalore are organized. The commercial areas in the city centre where Blank Noise interventions were initially organized, such as M.G. Road and Brigade Road, are dominantly inhabited by English speaking people, but in other parts of the city there are many who can only speak the local language, Kannada. After recognizing this, Blank Noise organized street interventions in such places, like the Majestic bus stand, and making flyers and stencils in Kannada. In order to do this, Blank Noise specifically called for volunteers who knew the local language.

The interventions might be in a non-elite space, but the main actors remain those from the middle class. Hemangini articulated the class issue in Blank Noise, saying “Like it or not, a lot of the people in Blank Noise are from the middle class and a lot of the people we have been talking to on the streets are of a certain class. What is the ethics in a middle class woman asking ‘why are you looking at me?’ to lower class men? It is if we already assumed that most perpetrators are lower class men while it is definitely not true.”

The reflexivity Hemangini shows led me to rethink the assumptions around digital activism. It is often dismissed as catering only to the middle class, privileging only one side of the digital divide. But then again, the class issue is also present in the physical sphere. If middle class youth mostly attracts their peers in their digital activism, is it problematic by default or is it only problematic when there is no accompanying reflection on the political implications of such engagement? How is it more problematic than the ethical dilemma of middle class people addressing their ‘Others’ in street interventions? Is the problem related to the sphere of activism (virtual versus physical), or is it more about the methods of engagement and the reflexivity required for it?

Hemangini told me that her dilemma is being shared and discussed with other members in Blank Noise’s core group, consisting of those who dedicate some time to reflect on the growth and development of the collective. They have no answer just yet, but they intend to continue reflecting on it. I have no idea what their future reflection looks like, but I do know that the class implications of the cyber sphere will be resolved with more than simply taking interventions to the streets. Considering that the actors of youth digital activism are, like it or not, urban, middle class, educated digital natives, Blank Noise’s reflection will indeed be relevant for all who is interested in this issue. And if you have your own thoughts on the strategies to resolve this dilemma, why don’t you drop a comment and reflect together with us?

This is the seventh post in the Beyond the Digital series, a research project that aims to explore new insights to understand youth digital activism conducted by Maesy Angelina with Blank Noise under the Hivos-CIS Digital Natives Knowledge Programme.

Beyond the Digital-Diving Into the Digital

First posted here

by Maesy Angelina in the Digital Natives

Previous posts in the ‘Beyond the Digital’ series have discussed the non-virtual aspects and presence of Blank Noise. However, to understand the activism of digital natives also require a look into their online presence and activities. This post explores how Blank Noise’s engagement with the public in their digital realm.

Through interviews and web-observations, I identified three ways in which Blank Noise and the virtual public engage with each other.

The first is by responding to the content provided by Blank Noise, such as commenting in posts or participating in polls or Facebook campaigns. There are cases where the comments turned the post into a space for intense discussion that raises interesting issues around street sexual harassment that are as significant for BN as it is for the viewers, such as Jasmeen’s aforementioned post of a harasser’s picture.

Yet, in other cases the comments ended up as a one-way communication that ignores thepossibility of turning into a public conversation. An example for this is Blank Noise’s ‘What does it take to be an Action Hero?’ event that I participated in. The event was hosted on Facebook from 25 June to 31 July 2010 and asked people to contribute a definition or a characteristic of an Action Hero, a woman who faces threat and experiences fear on thestreets of her city, but can devise unique ways to confront it. Blank Noise raised a potential conversation by asking questions for statements that tread on grey lines. A person who contributed ‘anyone who acts/protests against any form of behaviour which tends to outrage his/her sense of modesty’ was questioned on what modesty is and why it becomes a parameter, but it was not further responded. Furthermore, none of the other contributors attempted to raise or engage in such conversation.

I wondered what kind of meaning one could create from this limited way of participation and received several answers. It is a way to stay in touch and contribute to Blank Noise when one is not able to engage physically, as is the case for Laura Neuhaus after she left to continue her studies in the U.S. For others, it is a way to familiarize herself with the collective before deciding whether she wants to engage further. For the coordinators, it is to keep the momentum alive in between major interventions when they are committed to other priorities.

The second type of engagement is by actively producing content, like Rhea Daniel’s, a Mumbai-based design consultant, feisty poster contribution for theaforementioned online campaign or by sharing testimonials for the community blogs. Nandita Chaudury, a 29 year old researcher, wrote a story on her experience with street sexual harassment for Blank Noise Action Heroes community blog to show her support for BN but, more importantly, also to share experiences she wouldn’t share with anyone in real life.

Nandita said, “No one would want t share their most traumatic stories in public. I wouldn’t do it on my own blog, because I don’t want to come out yet, but I appreciate the space Blank Noise provides. After commenting in the posts and see how the discussion goes, I felt that it is a supportive space. Online contribution allowed me to stay anonymous while sharing my story to a wider public, so I felt confident in doing that.”

She further explained to me that reading others’ stories and receiving comments for hers made her feel less isolated and helped her healing process. Blank Noise’s cyber presence functions as a virtual support group for women affected by street sexual harassment, who relish a space where it is considered as a real issue and found more freedom to share given the anonymity granted by the Internet. Through their public testimonials, women demonstrate their agency in resisting harassments and undergo the transformation from victims into Action Heroes. Kelly Oliver (in Mitra-Kahn, unpublished: 17[1]) argued that writing experiences of a trauma, in this case street sexual harassment, helps the self heal by using speech and text to counter their emotions and exercise their agency;the process of empowerment that occurs hence establishes Blank Noise as a (cyber)feminist praxis. This is also a form of culture jamming: breaking the existing silence on street sexual harassment in the virtual public space.

Being a part of the virtual group helped Nandita to better cope with street sexual harassment in the physical public space, a sign that the virtual and the physical spheres mesh as reality for many of youth today. Nevertheless, this not the case for every youth. “Without real world activism, I would not have been able to deal with street sexual harassment in any real way,” said Annie, who found BN through the blogathon and has since become a coordinator.

Nandita and Annie’s stories are examples of how the virtual and physical spheres mesh in their lives, but also that the link between the two has points of disconnection that they are fully aware of. While Annie was ready to address the issue on the streets, Nandita was uncomfortable with doing so – but they were both went through a personal change enabled by Blank Noise’s cyber presence. Furthermore, the choices they made could be accommodated by Blank Noise through its online and offline interventions. This also shows a linkage or connection between the virtual and physical spheres in Blank Noise’s activities.

The online presence of Blank Noise serves multiple functions. It is a site for organization, mobilization, empowerment, and many possibilities for engagement that can be chosen based on one’s interest and abilities. It has value in itself, but it does not stand alone. It resonates with the street interventions in its potential to facilitate personal change at the individual level and beckons those who encounter Blank Noise to also extend their participation at the physical space – ifthey choose to do so. Blank Noise presents possibilities, but it is up for people to use and give meaning to it.

This is the sixth post in the Beyond the Digital series, a research project that aims to explore new insights to understand youth digital activism conducted by Maesy Angelina with Blank Noise under the Hivos-CIS Digital Natives Knowledge Programme.